It’s always fun to cross a border on a bike tour, even with a 24 hour ferry journey from Rome to Barcelona in between.

And Spain is very different to Italy.

Not just the parched, post-harvest, beige landscape but lots of other things that impact the life of a bicycle tourist.

The roads for one. They’re as smooth as silk in Spain, wide with a huge hard shoulder (emergency lane) to help us feel safely tucked away from the traffic, a refreshing change from the bumpy, narrow roads of Italy.

The drivers for two. The only other touring cyclist we met in Spain was a Canadian who literally could not stop talking in amazement about how incredibly nice the drivers were. He was blown away, completely gobsmacked!

We simply told him not to go to Italy!

Spanish drivers hang back politely, they allow a wide berth when they overtake bicycles and they give way at every opportunity. They’re right at the top of the Clare & Andy Driver Courtesy League, together with the Irish and the Dutch. (The Italians are at the bottom, with the Argentinians.)

In fact the roads are so good and the drivers are so nice that the cycling can even become a tiny bit boring … there are simply so few potholes to avoid.

And then there’s the famously late local eating patterns in Spain. A choice of lunch at three o’clock or dinner at nine doesn’t easily fit into the rhythm of a bike touring day.

But this time we switched into the culinary timezone straight away. Our ferry from Rome arrived in Barcelona at half past eight at night. By the time we’d found our hotel, unpacked, showered and changed we were wandering out in search of tapas at just after 10 o’clock. Far too late in most countries but perfect in Spain.

Having finished two previous bike tours in Barcelona in 2016 and 2021 we decided not to linger this time. After hurriedly doing the laundry and mending a puncture to Andy’s back wheel, we soon found ourselves nostalgically cycling up Avinguda Diagonal, this time out of the city.

Past experience had made us pretty nervous about escaping Barcelona, as the geography channels all the roads into two narrow valleys, one to the north and one to the south. Once again, we chose the southern route and tried to suppress the bad memories from our first attempt in 2016.

But this time it was a dream – cycle paths all the way, then out onto a smooth, wide secondary road up into the hills towards our hostal in La Pobla de Claramunt.

Clare was both relieved and impressed. Andy’s navigation skills must have improved a bit over the years … or more likely, they were terrible back in 2016!

This time he asked her to do just one unusual thing, to push her fully loaded bike into a lift in order to avoid a busy junction … a first for us!

Staying in a hostal in Spain does not mean sleeping in a shared dormitory with a bunch of smelly young travellers.

They are simple family run budget hotels, usually with a restaurant and other basic amenities, popular with workers but also great places for touring cyclists to stay.

The following morning, over a traditional Catalonian breakfast of Pa amb Tomàquet (crispy toast rubbed with garlic and ripe tomatoes, then drizzled with olive oil), Andy made a confession.

He had consistently told Clare that we didn’t need to worry about our Schengen days this year … we had loads left.

But, he now admitted that he’d left out of the calculations the ten days we’d spent cycling around the Normandy beaches in May. If we made it onto the ferry we’d booked from Bilbao there would only be one Schengen day in reserve.

And the next ferry was not until a week later.

Feeling a tiny but familiar knot develop in her stomach, Clare agreed that we’d have to crack on with some long cycling days. We might be able to turn north and explore the foothills of the Pyrenees later … IF and only IF we made good progress.

So Andy reluctantly replanned a route to follow the main roads, which were fast but dull. Even Clare started to find them a bit boring towards the end of the day, so as we neared Balaguer, our destination, she asked Andy to find a detour through the countryside instead.

Surprised but delighted, Andy soon found a way to loop around some small country roads that only added an extra 10 kilometres or so. But he might have failed to mention that some of the detour would be on ripio … the infamous Spanish gravel.

The gravel didn’t last too long and it became a glorious end to the day, the late afternoon sun warming our backs, the foothills of the Pyrenees beckoning us in the distance. A moment to reinforce the particular pleasure that only comes from enjoying a long bicycle tour together.

But the ripio came back to bite Andy when he woke up the next morning to find his front tyre completely flat, a tiny shard still embedded in the rubber. Surprisingly both our punctures have been in Spain, despite the quality of the roads!

This second puncture meant we’d now used up both our spare inner tubes in a matter of days. And there was likely to be more ripio to come.

As we wandered around the market, we were lucky to come across Cicles Perna, a tiny old-fashioned shop where several generations of the same family have been repairing bicycles since 1925.

Despite the language barrier, Josep Maria Badia Perna soon understood what we were looking for and dashed around the corner to his storeroom, returning several minutes later with a huge smile and two new tubes in exactly the right size.

Those Pyrenean foothills continued to look extremely inviting, so a couple of days later we felt we were making enough progress to swing north into their warm embrace.

We crossed into Aragon and made our way up to the stunning hill fortress town of Alquézar, whose name originates from al qaçr, the Arabic word for fort or castle.

Despite our previous travels in Spain, we hadn’t appreciated that the 8th century conquest of Hispania by the Moors had penetrated this far north, right up to the natural barrier of the Pyrenees.

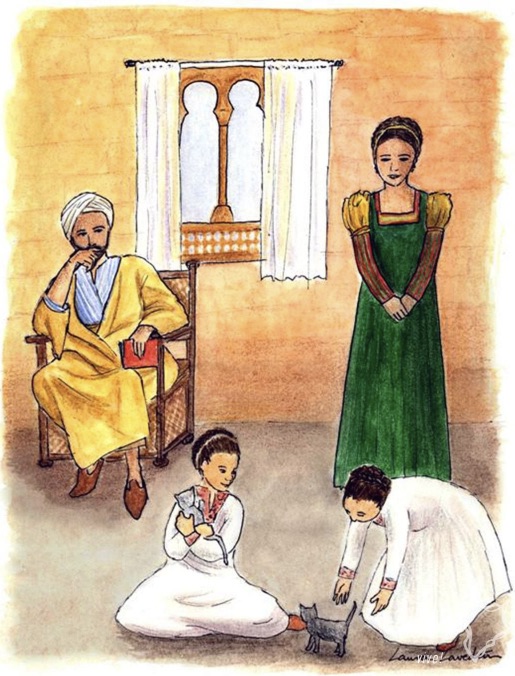

There were no ancient mosques to admire but we did come across an interesting story – the legend of Nunilo and Alodia, two young women from the 9th century.

Born to a Muslim father and a Christian mother of a wealthy family, these girls were raised as muslims at home but educated in a christian school. When their parents died they came under the care of their father’s brother, who tried to force them to renounce their mother’s faith and embrace Islam instead, including getting married to Muslim suitors.

They stubbornly refused, so the wicked uncle denounced them to the governor of Alquézar who had them imprisoned, before charging them with blasphemy and then chopping off their heads.

A bit harsh!

Photocredit: Turismo Somontano

That’s when the miracles started.

Left out in the wilderness for animals to eat, a miraculous light prevented any creature from touching their bodies. So their remains were dropped into a well … but the water from the well soon became known for its incredible curative powers.

This drew the attention of the Queen of nearby Navarre who snapped up the relics for the Monastery of Leyre, some 200 kilometres away. There, somewhat ironically, they were preserved in a famous ancient islamic casket that she had recently acquired as war booty.

Perhaps, even today, the people of Alquézar are still a bit sore at the loss of these bones, as their tourist information is happy to cast doubt on the efficacy of Nunilo and Alodia’s relics … or indeed any relics.

Instead of talking about miraculous cures, their information boards explain the economic importance of relics to medieval churches. The donations from grateful pilgrims were one of their main sources of income.

To attract more pilgrims and get more money, churches and monasteries had to outdo each other with ever more fantastical objects, even occasionally resorting to theft. Relics from martyrs such as Nunilo and Alodia were lucrative, but not nearly as lucrative as anything associated with Jesus.

Consequently there are hundreds of fragments from the True Cross, several burial shrouds and roughly three dozen Holy Nails spread around the world, including one we saw in Siena. In Medieval times several churches even claimed to offer a miraculous cure emanating from a piece of the Holy Foreskin, although these have subsequently disappeared.

But the tradition continues. In the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome we witnessed pilgrims queuing to receive protection from five pieces of sycamore twig, allegedly preserved from the Holy Manger itself.

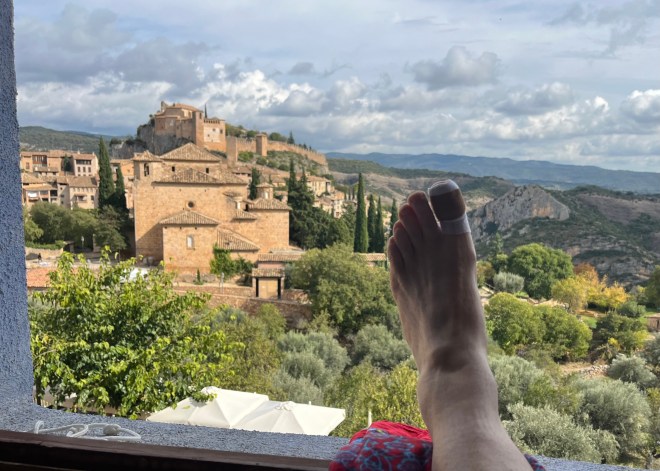

Andy could have done with a miraculous cure from the bones of Nunilo and Alodia, as it was in Alquézar that he revealed he was suffering from problems with his feet. The main issue was an ingrown big toenail that had developed a nasty infection.

Of course, being a stoic but stubborn man, he hadn’t mentioned this painful problem to Clare until it was oozing pus and until we were in a remote village in the hills, far away from civilisation.

Trying to hide her frustration, Clare dutifully squeezed out the pus but it was clear that he needed medical attention before we could continue. Of course, this small historic village didn’t have a pharmacy, let alone a doctor.

But Andy had a stroke of luck. The lovely 2* Hotel Santa Maria we were staying at is run by Daria, taking time out of her main career as a Spanish/English translator. She explained that there was a medical centre in Abiego, just 15km away. If that didn’t work we would have to cycle on to the hospital in Huesca, back down on the plain.

So we abandoned our rest day and rode through the hills to Abiego.

It was a Monday morning, normally an exceptionally busy time for British doctors after the weekend. Anticipating a long queue, we were amazed to discover that the medical centre was completely empty and we had the single doctor to ourselves. She didn’t speak any English but a combination of Clare’s Spanish and Google Translate helped us to understand her diagnosis and treatment.

The doctor prescribed antibiotic cream and a dressing to be picked up at the local pharmacy. Only problem? It was now midday and the pharmacy was closing for a nice long Spanish lunch, not opening again until 4pm.

Nervously, we jumped onto our bikes and dashed there as fast as we could, only to find that the doctor had already called ahead … so the pharmacist had delayed her lunch and was expecting us.

What great service! And all free, courtesy of our reciprocal health cards.

A quick call to Daria and we were soon back at the hotel, Andy’s toe enjoying a room with a view, Clare exploring the village.

Losing a rest day was not ideal as, despite our enjoyment of cycling in Spain, we were both starting to feel a bit bike weary and travel weary by now.

Rome had been our destination, our target, so psychologically this part of the journey always felt like a coda, a bit on the end. The kilometres in our legs and the constant packing and unpacking of our panniers were taking their toll.

As we ate dinner in the square that evening, we reflected that most of our rest days had been spent tramping around big cities, which however fascinating, added to the cumulative build up of exhaustion. The hills in Italy were a lot steeper than we’d expected and we’d reduced our daily distances as there were so many nice places to see … which meant more cycling days and less rest days.

We’d made a rooky error of not allowing ourselves enough days off the bike for proper relaxation. You’d have thought we’d have learnt that by now!

But the ride the next day through the canyons of Guara Natural Park to Boltana was enough to give any weary touring cyclist a second wind. It was stunning, one of our best days on a bike. Unlike the Pyrenees looming on the horizon, the wild beauty of this natural park does not lie in the height of its mountain tops but in the depth of its spectacular canyons, carved out by wind and water.

In the summer Guara is a mecca for fans of adventure sports … canyoning, mountain biking, rock climbing … but also for geologists, palaeontologists and archaeologists interested in ancient cave art, of which there are many fine examples.

We were simply content to pedal gently through the rugged landscape, to enjoy the golden eagles and Egyptian vultures soaring overhead and to peer down into the deep gorges.

Eventually we stopped for a picnic lunch in the tiny village of Arcusa.

Everything was closed but it was a lovely little square for a picnic … and for a party, judging by the many murals!

The following morning the young hotel receptionist told us that he was a keen cyclist too and asked which way we were going to Jaca. He was horrified to learn we planned to stay on the main road … warning us about racing traffic, bad drivers and a long tunnel.

I go on the Cotefablo Pass instead, he said, eyeing us dubiously. Nice roads, but you need good legs. We didn’t admit we were on electric bikes.

Consulting Komoot, we discovered that the Cotefablo Pass added an extra 30km and a hell of a lot of climbing to the day. Despite her experience in the tunnel on the Gotthard pass, Clare insisted we stick to the main road this time. Andy could only agree, his toe was still quite tender in his cycling shoes.

It turned out to be an inspired decision. Obviously that young man had never been to Italy. Here in Spain, the road was wide and smooth, the traffic light, the drivers courteous and the Túnel de Petralba so good, it actually became a highlight of the day.

As soon as the cameras spotted us pedalling into the tunnel, signs popped up warning drivers of the presence of Bicicletas en el Tunel.

The speed limit was immediately reduced to 60km/hour. Just for us!!

But there was hardly any traffic anyway … for most of the 3km we practically had this light, air conditioned tube to ourselves.

It was such a nice experience that we gave the controllers a cheery wave of thanks as we rode out through the cameras at the other end. Who cares if we were only waving at some artificial intelligence?

In Jaca another restorative treat awaited us. Lis, Andy’s sister, and her husband Ian had travelled all the way down to Spain on a first adventure in their new motorhome, just to see us for a day. There is nothing so rejuvenating as a long Spanish lunch with close family, catching up on news and laughing together. It was so good to see them, a proper rest day that got rid of any travel and cycling weariness for good.

Leaving Jaca there was an abrupt change to the season when daylight saving ended, signalling the official end of summer. Clouds shrouded the mountain tops, atmospheric and wintery, the air felt sharp and cold as we descended into a wide open valley.

Our route took us past the ‘Sea of the Pyrenees‘, a large reservoir controversially created by a Franco era dam. Controversial because it flooded several villages and a famous thermal spa resort, popular since Roman times.

But this was a weekend in late October, when the reservoir was at its lowest, allowing people a brief period to still enjoy bathing in the sulphurous waters, all be it without the luxurious changing rooms, restaurant or soporific music.

Just beyond the dam was our 1* hostal in the tiny, nondescript town of Yesa. We arrived at half past three but the patron cheerily informed us that it was still early for lunch and that the best thing to do would be to enjoy their Menu del Dias before we unpacked.

He was right. With families still rolling in an hour later the food was both delicious and very reasonable, a local bottle of wine included for good cheer. It was the kind of experience you only get if you go off the beaten track a little.

And we weren’t driving … or pedalling!

After Sunday morning coffee and croissants with the locals, an unremarkable ride took us to to Pamplona to enjoy wandering around the narrow streets of this lived-in city and to marvel at the madness of the famous running of the bulls.

By now we were feeling so restored and revived that Andy was happy to throw in a final detour on our last cycling day to Bilbao.

But once again, this was a detour that Clare actually enjoyed … around the contours of the Ullíbarri-Gamboa Reservoir on lakeside trails, wooded tracks and boardwalks.

Much fuller for the time of year, this lake is a popular recreational area full of beaches, summer camps and water sports. We didn’t meet a soul, it was utterly delightful.

Leaving the reservoir behind there was one final treat in store before we could celebrate the end of our journey outside the Guggenheim museum … a 15km descent down into the Nervión river valley towards Bilbao. Equally delightful and a wonderful finish.

As has often happened on all our bicycle tours, we were incredibly lucky to dodge the rain. Threatening all day, it poured down in a torrent just 15 minutes after we were safely tucked up in our hotel room.

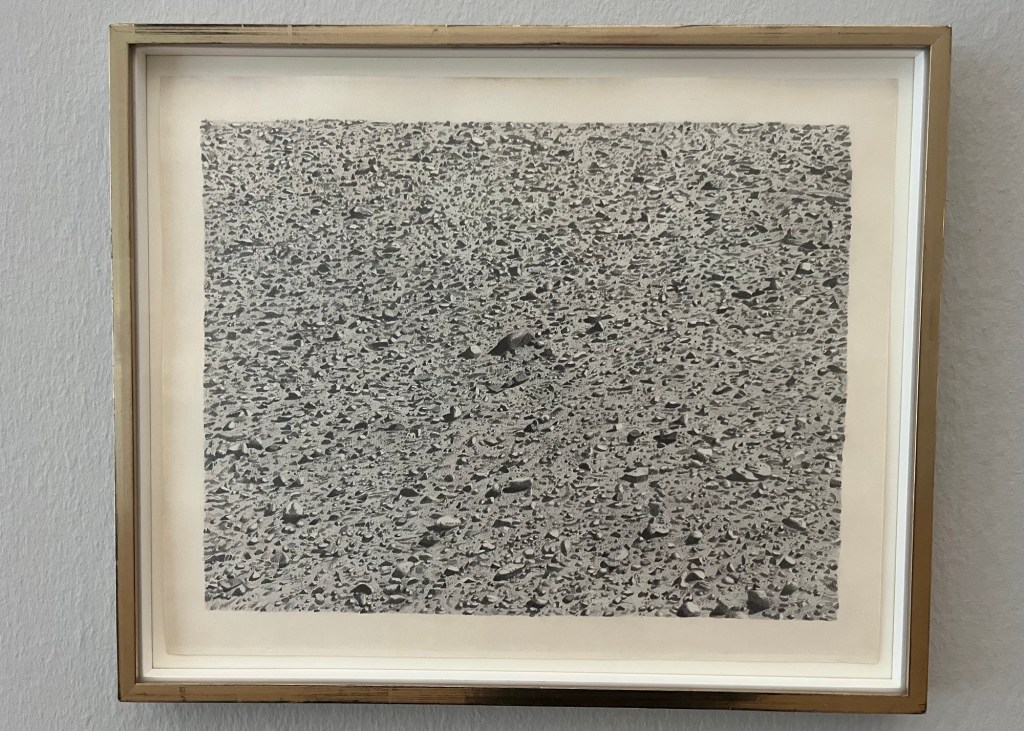

The famous Guggenheim properly lives up to its reputation, both the building (one of the most important architectural designs of the late 20th Century) and the impressive art collection, which is often on an enormous scale.

The Guggenheim makes Bilbao worth a visit on its own but the special Basque culture adds to the charm, especially as it has a surprisingly English twist.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries British ships would bring coal to Bilbao and return with iron and steel. In those ships came thousands of miners and engineers, many of them from north-east England, many deciding to stay, many passionate about the sport that had by now become so deeply ingrained in working class culture … football. Students from Bilbao travelled in the other direction to study and they quickly grew to love the game themselves.

Thus in 1898 a group of British migrant workers and returning Basque students founded Athletic Club (using the distinctly English spelling instead of Club Atlético). The football club has since become unique in the world for only signing players who have been born or developed in the Basque region, through its cantera (meaning quarry) of youth development and a deep talent spotting network in grass roots football.

Despite this self imposed constraint, Athletic Club is proud to be one of only three clubs (the other two being Barcelona and Real Madrid) that have never been relegated from La Liga, the top league in Spain. Champions 8 times, they’ve also won the Copa del Rey (the Spanish FA Cup) on 24 occasions, most recently in 2024.

The connection between Athletic Club and their English roots remains strong, with a special bond developing between their fans and those of Newcastle United after a match in 1994. Athletic won the game in Bilbao 1-0 for a 3-3 aggregate scoreline, winning the overall tie on away goals.

But immediately after the final whistle the Basque home fans invaded the pitch, not to make trouble, but to applaud the Geordies and then went on to entertain them late into the night. They were so kind. They laid out the red carpet for us and wouldn’t let us buy a single drink, reported one grateful Newcastle fan, I came back with as much money as I went out with.

This was all to repay a favour.

Apparently, some Athletic supporters had missed their transport back to Bilbao from Newcastle a couple of weeks earlier after the first leg. They had been put up by a family in Newcastle and the story of the warmth of Geordie hospitality had made its way back to Bilbao.

It’s an unusual friendship that endures to this day.

As we weren’t wearing the famous black and white stripes of Newcastle United, we were happy to pay for our own celebratory drinks.

Celebrating boarding the ferry the next morning, just the one day inside our Schengen limit.

Celebrating that this was genuinely the end of our bike tour with no pedalling needed through two damp, cold November days to get back home from Portsmouth.

Clare’s brother, Matthew had kindly offered to meet us off the ferry in his campervan and even drive us back to Bath the following day. We stayed overnight with Matthew and his wife Nicola at their lovely home in the New Forest, enjoyed a delicious roast chicken dinner and, once again, felt rejuvenated by the warm embrace and easy conversation of close family.

From Bath to Rome (and back) we have pedalled 3,291 kilometres, our second longest bike tour.

It was also our 10th year of meandering slowly around different parts of the world on a bicycle.

In those ten years we’ve pedalled for just over 24,000 kilometres or just under 15,000 miles. 60% of that distance was on our faithful Ridgeback touring bikes, 40% on our new Cube e-bikes. We’ve climbed 229,000 metres which is roughly 26 Everests. We’ve ridden on 366 days, a leap year, with nearly 1500 hours in the saddle, cycling across 22 different countries on 5 continents.

On the ferry back to the UK, we decided that maybe, just maybe, this is the right moment to hang up our panniers and do something else instead. Whatever happens we have already made different travel plans for 2026, so we won’t be re-hitching our panniers to our worn out bike racks until 2027 at the earliest.

Like a sportswoman reluctant to retire from the sport she loves, that last day of cycling to Bilbao was enough to make Clare fall back in love with bicycle touring … so she is the one who is now pushing for more adventures.

She says there are a lot more iMax views from our handlebars to enjoy.

She’s suggested more Spain. She’s also suggested Slovenia and Central Europe.

But she’s given Andy an ultimatum … two months and 2000 kilometres is the absolute maximum!

If we do decide to hang up our panniers, then this is also our last Avoiding Potholes blogpost.

Thank you from the bottom of our hearts for following us through these little adventures, for all your comments and words of encouragement. We hope you’ve enjoyed it at least half as much as we have!

So … Hasta la Vista (until next time). Probably … possibly … who knows?

Clare and Andy

Bath to Rome (and back)

3,291 kilometres pedalled

31,146 metres climbed

173 hours in the saddle over 68 days

2 punctures, 1 broken seat post, 1 new set of brakes